The Tebtunis Papyri Collection

Overview

The Tebtunis papyri form the largest collection of papyrus texts in the Americas. The collection has never been counted and inventoried completely, but the number of fragments contained in it exceeds 26,000.

The Center for Tebtunis Papyri strives to enhance understanding of the collection by providing information about the sites where the papyri were found, the intellectual and physical history of the collection, and the contents of the papyri contained in it. A particularly interesting aspect of the collection is that it contains many related groups of texts, which creates context. We have given emphasis to such texts on this site.

The project of conserving, cataloguing, and imaging these papyri has been supported by generous grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities as part of the APIS project (now incorporated in the papyri.info database).

This project is the result of collaboration among papyrologists at a number of American universities to integrate their digital images and detailed catalogue records into a virtual library. These online records provide information pertaining to the physical and textual characteristics of each papyrus, corrections to previously published papyri, and notes about re-publications.

The Berkeley and Regional Partners Papyrus Database includes information from the APIS (papyri.info) project that is currently housed on the servers of Berkeley IT. It includes papyri from The Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley as well as records for papyri in select collections in the western United States. This metadata was produced or collected in conjunction with APIS-Berkeley’s “Regional Partners” initiative. The Badè Museum of Biblical Archaeology (Pacific School of Religion), California State University (Sacramento), Stanford University, and Washington State University participated in this initiative. The Badè Museum papyri have since been sold.

Crocodile mummies

Texts of village scribes

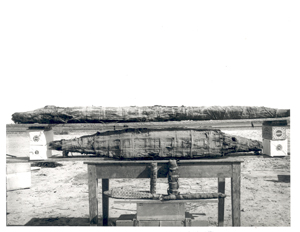

Many texts in the Tebtunis Papyri Collection were found in the cartonnage of crocodile mummies. The majority of these texts originate from the archive of the komogrammateus (village scribe) of Kerkeosiris and date through the end of the second century BCE. Central within this body of documents are the papers of Menches, who performed the duties of komogrammateus of Kerkeosiris between about 120 and 110 BCE.

Texts of ancient village officials

Apart from the Menches papers, there are quite a few documents from crocodile mummies belonging to the papers of other Kerkeosiris village officials, such as the epistates (overseer and tax collector for the ruler) and the archiphylakites (roughly comparable to a modern police chief).

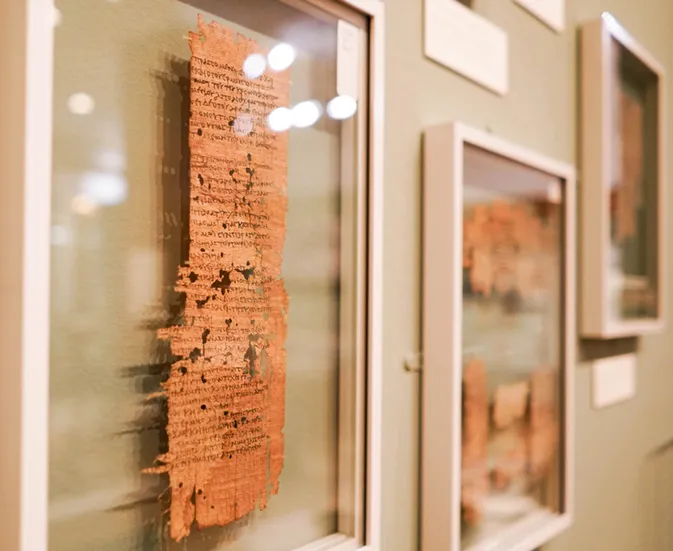

An example of such a text is P. Tebt. 52, circa 114 BCE, which is a petition addressed to Polemon, the epistates of Kerkeosiris. In it, a villager named Tapentos complains to Polemon that documents were stolen from her house. Unfortunately, only the beginning of the petition has survived:

To Polemon, epistates of Kerkeosiris, from

Tapentos daughter of Horos, of the same village.

An attack was made upon my dwelling by Arsinoe

and her son Phatres, who went off with the contract relating to my

house and other business documents. Therefore I am seriously ill, being in want of the necessaries of life and bodily . . .

Here the papyrus breaks off.

Crocodile mummies found at Tebtunis. Photograph 1899/1900. Courtesy of the Egypt Exploration Society

Texts of crocodile priests?

A separate group of crocodile mummy texts in the collection includes 45 Greek documents, mostly private, from the first half of the first century BCE. These texts came from just five crocodile mummies that had been buried in two adjacent tombs, strongly suggesting one composite burial.

Along with these Greek papyri, a few demotic and bilingual papyri were found in the crocodiles. They probably originally belonged to the priests of the crocodile god Soknebtunis, who mummified the crocodiles. The priests used their own waste papyri in the mummification process, as well as papyri belonging to other people such as Menches, the village scribe of Kerkeosiris.

The priests of Soknebtunis also buried large demotic papyri alongside the crocodile mummies, possibly as offerings to Soknebtunis. These demotic papyri contained the annual rules of the fraternity of priests.

Human mummies papyri

This group of papyri comes from the cartonnage covering human mummies. These texts date from the third and second centuries BCE. As in the case of the papyri from the crocodile mummies, we find, among other things, the remains of various official papers.

Texts from scribes and guards (officials)

Quite a considerable number of texts can be traced back to Oxyrhyncha, a small village to the north of Tebtunis. Among these are texts from village officials, such as the komogrammateus (village scribe) and the phylakes (guards).

P. Tebt. 771, from the mid-second century BCE, is a petition from an inhabitant of Oxyrhyncha to the King and Queen of Egypt. Fragments of two copies of this petition have survived in the same mummy cartonnage:

To King Ptolemy and Queen Kleopatra, his sister, the mother-loving gods, greeting. From Petesouchos son of Petos, Crown cultivator from the village of Oxyrhyncha in the division of Polemon in the Arsinoite nome. I live in Kerkeosiris in the said nome, and there belongs to me in the aforesaid village of Oxyrhyncha a house

inherited from my father, possessed by him for the period of his

lifetime and by myself after his decease up to the present time

with no dispute. But Stratonike daughter of Ptolemaios, an

inhabitant of Krokodilon polis in the aforementioned nome, mischievously wishing to practise extortion on me, coming with other persons against the aforesaid house, forces her way in before any judgement has been given and. . .in the village about. . .the house, coming in and laying claim to it wrongfully. I therefore pray

you, mighty gods, if you see fit, to send my petition to

Menekrates, archisomatophylax and strategos, so that he may order

Stratonike not to force her way into the house, but, if she

thinks she has a grievance, to get redress from me in the proper

manner. If this is done, I shall have received succour. Farewell.

Mummy cartonnage (heads, pectorals, and feet). Photograph 1899/1900. Courtesy of the Egypt Exploration Society.

Texts from official village archives

In addition to the Greek texts described above, there are large numbers of demotic papyri from the cartonnage of human mummies, including several official registers of tax payments. These papyri therefore come from one or more official archives, perhaps the same archives as the Greek papyri.

We hypothesize this because early in the Ptolemaic period, during the third and early second centuries BCE, it was quite common for officials to keep administrative records in the Egyptian language rather than in Greek. Only later did Greek come to predominate as the administrative language.

Tebtunis town papyri

Compared to the other three groups, these texts are the most diverse. For one thing, the town papyri yielded most of the literary fragments. Among them are more than a dozen fragments of Homer (Iliad and Odyssey), Demosthenes, and Dictys Cretensis.

A substantial portion of the papyri from the town concerns the priests of Soknebtunis.

Among other texts found in the town are a variety of legal documents: contracts, petitions, declarations, and tax receipts. The majority of these documents date to the first three centuries CE, when Egypt was under Roman rule.

A petition to a governor

P. Tebt. 330 is a petition addressed to the strategos (district governor) by Ptolemaios, son of Patron. The text is not dated, but we know that the strategos Bolanos served between 196 and 198 CE. In the text, Ptolemaios reports the burglary of his house:

To Bolanos, strategos of the division of Themistos and Polemon of the Arsinoite nome, from Ptolemaios son of Patron, of the village of Tebtunis.

After being absent, when I returned to the village, I found my house pillaged and everything that was stored

in it carried off. Wherefore, being unable to submit to this, I apply to

you and ask that this petition may be entered on the register in

order that, if anyone is proved to be the culprit, he may be

held accountable to me.

Farewell.

A petition to a centurion, in Greek

In the petition P. Tebt. 333, a woman named Aurelia Tisais informs a centurion (military officer) of the disappearance of her father and brother on a hunting expedition. The text is dated to December 22, 216 CE:

To Aurelius Julius Marcellinus, centurion, from Aurelia Tisais, whose mother is Tais, formerly styled as an inhabitant of the village of Tebtunis in the division of Polemon.

My father Kalabalis, Sir, who is a hunter, set off with my brother

Neilos as long ago as the 3rd of the present month to hunt hares,

and up to this time they have not returned. I therefore suspect that

they have met with some accident, and I present this statement,

making this matter known to you, in order that if they have met

with any accident the persons found guilty may be held accountable to me. I happen to have also presented a copy of this notice to the

strategos Aurelius Idiomachos to be placed on the register.

The 25th year of Marcus Aurelius Severus

Antoninus Caesar the lord, Choiak 26.

Demotic papyri

Again, along with these Greek papyri, a few demotic papyri were found in the town. These papyri mostly belong to two private archives, one of the oil merchant Phanesis, son of Nechthuris, dating to the late third century BCE, the other of Soknopis, son of Sigeris, dating to the late second and early first centuries BCE.

The demotic papyri are earlier than most of the Greek papyri from the town. The use of Greek became more common later during the Ptolemaic and Roman periods.

Hearst papyrus

About the Hearst papyrus

Apart from the Tebtunis papyri, The Bancroft Library houses several other important manuscripts from ancient Egypt. One is the papyrus known in the Egyptological world as the Hearst Medical Papyrus. For the unusual circumstances of its discovery, see the next section.

The Hearst Papyrus dates to the first half of the second millennium BCE. It contains, in hieratic Egyptian writing (a cursive form of hieroglyphic writing), 18 columns with medical prescriptions. The ailments for which cures are offered range from “a tooth that falls out” to a “remedy for treatment of the lung” to bites by human beings, pigs, and hippopotami.

The papyrus, which bears a great resemblance to another Egyptian medical papyrus (the so-called Papyrus Ebers), entered Egyptology’s Hall of Fame in 1905, when George Reisner published plates illustrating the papyrus along with an introduction and vocabulary. While the contents of the papyrus have since been studied extensively, the physical papyrus itself, which is in surprisingly good condition, has not yet been the object of careful analysis.

Purchase and provenance

In the 1905 publication of the papyrus, George Reisner described the purchase of the papyrus as follows:

In the spring of 1901, a roll of papyrus was brought to the camp of the Hearst Egyptian Expedition near Der-el-Ballas by a peasant of the village as a mark of his thanks at being allowed to take sebach from our dump-heaps near the northern kom. In my absence at Girga, he left the roll with Lythgoe until I should return. He said that he had found the roll while digging for sebach two years before, that he had put it away in a cupboard in his house and forgotten it. He had found the roll in a pot among the house walls between the southern kom and the southern cemetery. There was nothing else in the pot except this roll. His description of the pot did not enable us to identify its type.

In my opinion, considering the man, there can be no reason to doubt these statements. The man attached no value to the papyrus. He did not come again until sent for six months later; and he gratefully accepted the price given him without any attempt whatever at bargaining. The roll was brought to Lythgoe, brutally tied up in the end of a native head-cloth (suga), and had, of course, been carried in a similar manner from the place where it was found to the village. The damage done to pages XVI to XVIII which were on the outside of the roll was due to this treatment. The pieces broken off during the trip from the sebach digging to the village were lost; but those broken off during the trip to the house, were rescued from the folds of the head-cloth by Lythgoe.

On my return to Der-el-Ballas, the papyrus was unrolled by Dr. Borchardt and myself. The roll had not been opened since antiquity as was manifest in the set of the turns, the fine dust, and the casts of insects. The beginning of the roll was inside. (...)

Archives & dossiers

The Tebtunis Papyri contain various groupings that originate from a single archive or can be collected to form a dossier. So far, several groups of texts have been identified, including the Papers of the Crown Tenants of Oxyrhyncha, Patron dossier, Adamas papers, and Literary texts, as well as the Menches Archive and the Papyri Concerning the Priests of Soknebtunis detailed below.

The Menches Archive

A considerable portion of the papyri from the Tebtunis crocodile mummies once formed part of the archive of the komogrammateus (village scribe) of the nearby village of Kerkeosiris. Most documents date from the years 115-112 BCE, when a certain person named Menches performed the duties of komogrammateus. Berkeley also holds documents from earlier and later years of Menches’s unknown predecessor and his successor Petesouchos (P. Tebt. I 29, 77, 78). The Menches papers can be divided in two groups, administrative documents and correspondence.

Administrative documents of Menches

The administrative documents form the core of the Menches papers. They consist of (often lengthy) reports, in which Menches details the state of affairs of every square meter of Kerkeosiris. He recorded the fiscal category to which each plot of land belonged, its holder, the crops sown upon it, and payments due to the state.

Menches focused upon the royal domain (Crown land), from which the Crown could expect the most revenues. Each year, Menches drew up several documents in which he presented the crops with which the Crown land had been sown in a given year. He also composed extensive reports in which he listed all landholders in this category (the Crown tenants) with the size of their plot and the amounts (rent and land taxes) due to the Crown. An example of a report in which Menches gave a summary account of the crops sown on Crown land is P. Tebt. I 153.

Correspondence of Menches

The other part of the Menches papers consists of correspondence. This correspondence includes official letters that were addressed to Menches by his superiors and peers in the Ptolemaic bureaucracy.

An interesting example is P. Tebt. I 10, dated to August 20, 119 BCE. It is a letter sent by Asklepiades, probably the basilikos grammateus (royal scribe), Menches’s superior in the nome capital, to Marres, the topogrammateus (district scribe). In it, Asklepiades informs Marres that Menches has been appointed to the post of komogrammateus (village scribe) of Kerkeosiris by the dioiketes, the highest official of Ptolemaic Egypt.

Another interesting feature of the Menches Papers is that they contain drafts of texts sent by Menches to colleagues. Unlike the finished versions dispersed to their recipients, these drafts remained in Menches’s archive, and thus they give us a (rare) chance to examine Menches’s expressions. A fine specimen of such a text is P. Tebt. I 15, the first draft of which (August 18, 114 BCE) informs Horos about events surrounding an attack upon another village official, the epistates Polemon. For examples of other drafts of letters sent by Menches, see P. Tebt. I 9, 14, 38.

Finally, the Menches Papers contain quite a few petitions addressed to Menches by villagers who were wronged in various ways and who petitioned Menches to obtain redress. These petitions provide a lively view on village life in Kerkeosiris at the end of the second century BCE. The reasons for petitioning Menches ranged from violence to theft to being hindered in one's agricultural tasks. For examples of other petitions, see P. Tebt. I 40, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, and 51v.

Papyri concerning the priests of Soknebtunis

During their 1899/1900 expedition for UC Berkeley, Grenfell and Hunt uncovered a substantial group of papyri in the houses within the temple area of Tebtunis. Dating to the second century CE, the texts inform us about the lives of the priests of the crocodile god Soknebtunis, the principal deity worshipped in the temple.

P. Tebt. 294 (from 147 CE) is an application by Pakebkis, son of Marsisouchos, for the purchase of the office of chief priest (prophetes).

Two documents are concerned with the circumcision of aspirants to the priestly office. The first text (P. Tebt. 292) is an application to the strategos in which Isidora desires that her son and another relative be circumcised. She asks the strategos to address a letter to the high priest. The second text (P. Tebt. 293, circa 187 CE) is a sworn declaration furnished by four priests of Tebtunis to the strategos, certifying that a candidate for circumcision was indeed of priestly lineage and otherwise a suitable candidate.

P. Tebt. 304 (167/168 CE) suggests that priestly life in Tebtunis also had its more dangerous sides. In this text Pakebkis informs the dekadarches of an assault made upon him and his brother.

For other texts from the dossier of the Priests of Soknebtunis, see P. Tebt. 295, 296, 299, 300, 301, 307, 308, 311, and 315.

Images of papyri

These images are a small sample of the images available in this project.

P. Tebt. I

9 Application by Menches for the post of komogrammateus

10 Official letter from Asklepiades

14 Draft of a letter from Menches to Horos

15 Drafts of two letters from Menches to Horos

17 Letter from Polemon to Menches

18 Letter from Polemon to Menches

19 Letter from Polemon to Menches

20 Letter from Polemon to Menches

21 Letter from Polemon to Polemon

22 Letter from Taos to Menches

23 Letter from Marres to Menches

25 Copy or draft of an official letter

29 Draft of a letter to the chrematistai

31 Correspondence concerning a change of ownership

38 Official letter from Menches to Horos

39 Petition from Apollodoros to Menches

40 Petition from Pnepheros to Amenneus, forwarded to Menches

44 Petition from Haryotes to Menches

45 Petition from Demas to Menches

46 Petition from Harmiysis to Menches

48 Petition from Horos to Menches

49 Petition from Apollophanes to Menches

50 Petition from Pasis to Menches

51 Petition from Horos to Menches

52 Petition from Tapentos to Polemon

53 Petition from Horos to Petesouchos

55 Letter from Mousaios to Menches

153 Register of the crops of crown land

P. Tebt. II

286 Copy of proceedings of a trial

293 Report on an application for circumcision

294 Application for the purchase of a priestly office

295 Register of priestly offices

296 Purchase of a priestly office

307 Receipt for tax on sacrificial calves

308 Receipt for price of papyrus

426 Homer, Iliad 2, 33-37; 46-52; 55-60

429 Homer, Iliad 13, 340-350; 356-37

430 Homer, Iliad 16, 401-405; 418-430

431 Homer, Odyssey 11, 428-440

432 Homer, Odyssey 24, 501-508

679 Treatise on the medical properties of plants [with colored illustrations]

P. Tebt. III

711 Official letter from Theon

712 Official letter from Herakleides

715 Official letter from Petosiris (komogrammateus of Oxyrhyncha)

745 Official letter from Agathon

746 Official letter from Agathon

747 Official letter from Agathon

748 Official letter from Agathon

749 Official letter from Agathon

763 Private letter from Ptolemaios

771 Petition to the king and queen

896 Philosophical disquisition or dialogue ?

Glossary of terms

archiphylakites

“chief guard”; head of the village guards

aroura

Egyptian area measure, measuring 2756 square meters (about half a football field); a person could live on the net produce of 2 arouras

Arsinoite nome

administrative unit comprising the modern Fayum basin; the Arsinoite nome was divided in three “divisions”: the Division of Herakleides, the Division of Themistos, and the Division of Polemon (southern part); Tebtunis, Kerkeosiris, and Oxyrhyncha were all situated in the Division of Polemon

artaba

Egyptian dry measure of variable capacity, about 40 liters; a person could live on about 10 artabas of wheat per year

basilikos grammateus

“royal scribe”; nome official, responsible for administration of the Crown revenues from the nome

cartonnage

material from which Egyptian funerary masks and other parts of mummy cases were made from the First Intermediate Period onward; made of layers of linen or papyrus covered with plaster; in Fayum some painted mummy portrait panels were made of cartonnage

cleruchic land

land granted by the king to soldiers (and a small number of civil servants) as a reward for services rendered

demotic

a more cursive form of hieratic writing, which developed from hieroglyphic writing; demotic writing appeared around 600 BCE and began to replace hieratic writing in administrative contexts, whereas hieratic often continued to be used in religious texts until Coptic replaced both

dioiketes

highest-ranking official of Ptolemaic Egypt; “manager” of the country

drachma

the basic unit of currency in Graeco-Roman Egypt

ephebes

in Classical Greece, young men undergoing training in the gymnasium; in a looser sense prevailing in Graeco-Roman Egypt, those enrolled in a privileged class of citizens of Alexandria, membership in which also conferred tax benefits

epistates

overseer, supervisor; while there were several “overseers” on various levels of the administration, the epistates referred to most frequently is the epistates of the village, who could be called the local police chief

hieratic

a cursive form of hieroglyphic writing whereby original hieroglyphic signs were simplified, even down to a single stroke or dot, and signs were sometimes combined for simplicity

keramion

liquid measure of varying capacity

komarches

village official, more or less “mayor”

komogrammateus

village secretary, whose primary responsibility was the administration of the Crown revenues deriving from the lands of his village

metropolis

chief town of a nome

nome

geographical and administrative unit, more or less a province

obol

monetary unit, equal to 1/6 drachma

ostracon

(plural ostraca) a sherd of pottery, usually from broken vases, urns, or other vessels, or a fragment of stone; used as a writing surface in place of papyrus, especially for short documentary texts

prefect

governor of Egypt in the Roman period

prophetes

priestly office

sacred land

land granted by the king to gods (temples)

sitologos

official in charge of the local granary; responsible for grain revenues

strategos

highest-ranking nome official

talent

monetary unit, equal to 6,000 drachmas

topogrammateus

district secretary