The Oral History Center is deeply engaged with the teaching mission of the university. Through our educational programs, we are training generations of scholars in the possibilities of oral history. This section of the website is about learning how to do oral history. It includes information on everything from day and weeklong workshops, to remote interviewing tutorials, interview tips, and graduate internship and fellowship opportunities.

If you are a K-16 educator who wants to use oral history in the classroom, or an undergraduate seeking an internship, employment, or other opportunities, please visit our K-16 section.

More about our educational programs

Advanced Institute

We are now accepting applications for our 2024 Advanced Institute on a rolling basis. Please apply early, as spots fill quickly.

The Oral History Center is offering a virtual version of our one-week Advanced Institute on the methodology, theory, and practice of oral history. This will take place Aug. 5-9, 2024.

The cost of the Advanced Institute has been adjusted to reflect the online nature of the program. Tuition is $600.

The institute is designed for graduate students, postdoctoral fellows, university faculty, independent scholars, and museum and community-based historians who are engaged in oral history work. The goal of the institute is to strengthen the ability of its participants to conduct research-focused interviews and to consider special characteristics of interviews as historical evidence in a rigorous academic environment.

We ask that applicants have a project in mind that they would like to workshop during the week. All participants are required to attend small daily breakout groups in which they will workshop projects.

In the sessions, we will devote particular attention to how oral history interviews can broaden and deepen historical interpretation situated within contemporary discussions of history, subjectivity, memory, and memoir.

Overview of the week

The institute is structured around the life cycle of an interview. Each day will focus on a component of the interview, including foundational aspects of oral history, project conceptualization, the interview itself, analytic and interpretive strategies, and research presentation and dissemination.

Instruction will take place online tentatively from 8:30 a.m. to 2 p.m. Pacific time, with breaks woven in. There will be three sessions a day: two seminar sessions and a workshop. Seminars will cover oral history theory, legal and ethical issues, project planning, oral history and the audience, anatomy of an interview, editing, fundraising, and analysis and presentation. During workshops, participants will work throughout the week in small groups, led by faculty, to develop and refine their projects.

Participants will be provided with a resource packet that includes a reader, contact information, and supplemental resources. These resources will be made available electronically prior to the institute, along with the schedule.

Applications and cost

The cost of the institute is $600. We are offering a limited number of participants a discounted tuition of $300 for students, independent scholars, or those experiencing financial hardship. If you would like to apply for discounted tuition, please indicate this on your application form and we will send you more information.

Please note that the OHC is a soft-money research office of the university, and as such receives precious little state funding. Therefore, it is necessary that this educational initiative be a self-funding program. Unfortunately, we are unable to provide financial assistance to participants other than our limited number of scholarships. We encourage you to check in with your home institutions about financial assistance; in the past we have found that many programs have budgets to help underwrite some of the costs associated with attendance. We will provide receipts and certificates of completion as required for reimbursement.

Applications are accepted on a rolling basis. We encourage you to apply early, as spots fill up quickly.

Questions

Please contact Shanna Farrell with any questions.

Intro workshop

The 2025 Introduction to Oral History Workshop will be held virtually via Zoom on Friday, Feb. 28 from 8:30 a.m. to 2:30 p.m. Pacific Time, with breaks woven in. Applications are now open and being accepted on a rolling basis. Please apply early, as spots fill up quickly.

This workshop is designed for people who are interested in an introduction to the basic practice of oral history and learning best practices. The workshop serves as a companion to our more in-depth Advanced Oral History Summer Institute held in August 2025.

The workshop focuses on the “nuts-and-bolts” of oral history, including methodology and ethics, practice, and recording. It will be taught by our seasoned interviewers and include hands-on practice exercises. Everyone is welcome to attend the workshop. Prior attendees have included community-based historians, teachers, genealogists, public historians, and students in college or graduate school.

Tuition is $175. We are offering a limited number of participants a discounted tuition of $80 for students, independent scholars, or those experiencing financial hardship. If you would like to apply for discounted tuition, please indicate this on your application form and we will send you more information. Please note that the OHC is a soft-money research office of the university, and as such receives precious little state funding. Therefore, it is necessary that this educational initiative be a self-funding program. Unfortunately, we are unable to provide financial assistance to participants other than our limited number of scholarships. We encourage you to check with your home institutions about financial assistance; in the past we have found that many programs have budgets to help underwrite some of the costs associated with attendance. We will provide receipts and certificates of completion as required for reimbursement.

Applications are accepted on a rolling basis. We encourage you to apply early, as spots fill up quickly.

If you have specific questions, please contact Shanna Farrell.

Remote interviewing

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, OHC oral historians have developed new practices and procedures to enable remote interviewing and to consider the implications of this practice. In the documents below, we provide our latest guidelines on topics including: remote interviewing with Zoom, tips for getting started in oral history while sheltering in place, and more to come. We welcome feedback, questions, and suggestions for additional topics to cover.

Remote interviewing with Zoom

These protocols were developed to facilitate remote recording of narrators of the highest quality available during the COVID-19 pandemic. We developed these protocols for the Zoom video conference platform using both audio and video. We also provide instructions for additional, backup audio recordings. Interviewers, or the hosts of the interviews, will need to have a professional Zoom license; narrators need only access to a computer or telephone.

Available for download: Remote Interviewing with Zoom

Recording with Zoom

Learn how to conduct and record interviews on Zoom with this webinar developed by Paul Burnett and taught by experts in oral history, who interviewed remotely during shelter-in-place. Watch the webinar.

Articles about remote interviewing

Storytelling at a distance: staying connected while we are apart

Oral History provides a way for people to see the world through someone else’s eyes. In this article posted toward the beginning of shelter-in-place in April 2020, Amanda Tewes shares storytelling questions anyone can use to frame oral history life interviews and to have more meaningful conversations — even at a distance.

In this article from March 2021, Shanna Farrell talks about the genuine human connection forged between an interviewer and a narrator, the challenges of establishing rapport remotely, and how it can be done.

Looking to the future of oral history work

Remote interviewing has enabled opportunities that didn’t exist before. Amanda Tewes sorts out the pros and cons of remote interviewing in this article from May 2021.

Interviewing tips

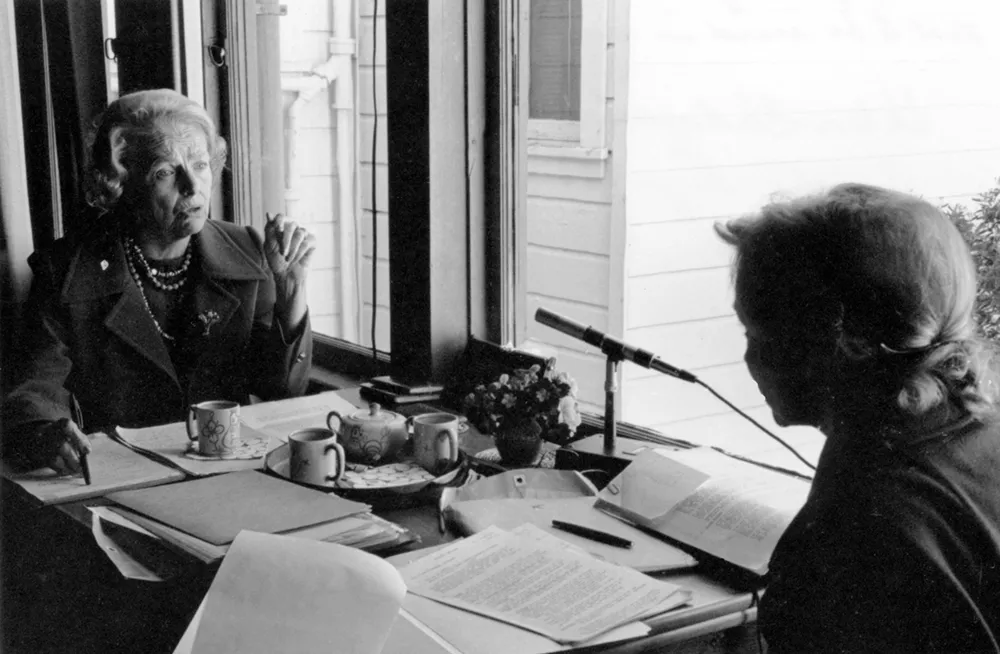

During transformative times in history like these, it’s important to document the lives of everyday citizens. Willa Baum (pictured above), a pioneer in oral history and former director of the Oral History Center, shared the following tips on conducting oral histories.

- An interview is not a dialogue. The whole point of the interview is to get the narrator to tell her story. Limit your own remarks to a few pleasantries to break the ice, then brief questions to guide her along. It is not necessary to give her the details of your great-grandmother's trip in a covered wagon in order to get her to tell you about her grandfather's trip to California. Just say, "I understand your grandfather came around the Horn to California. What did he tell you about the trip?"

- Ask questions that require more of an answer than "yes" or "no." Start with "why," "how," "where," "what kind of ..." Instead of "Was Henry Miller a good boss?" ask "What did the cowhands think of Henry Miller as a boss?"

- Ask one question at a time. Sometimes interviewers ask a series of questions all at once. Probably the narrator will answer only the first or last one. You will catch this kind of questioning when you listen through the tape after the session, and you can avoid it the next time.

- Ask brief questions. We all know the irrepressible speech-maker who, when questions are called for at the end of a lecture, gets up and asks five-minute questions. It is unlikely that the narrator is so dull that it takes more than a sentence or two for her to understand the question.

- Start with questions that are not controversial; save the delicate questions, if there are any, until you have become better acquainted. A good place to begin is with the narrator's youth and background.

- Don't let periods of silence fluster you. Give your narrator a chance to think of what she wants to add before you hustle her along with the next question. Relax, write a few words on your notepad. The sure sign of a beginning interviewer is a tape where every brief pause signals the next question.

- Don't worry if your questions are not as beautifully phrased as you would like them to be for posterity. A few fumbled questions will help put your narrator at ease as she realizes that you are not perfect and she need not worry if she isn't either. It is not necessary to practice fumbling a few questions; most of us are nervous enough to do that naturally.

- Don't interrupt a good story because you have thought of a question, or because your narrator is straying from the planned outline. If the information is pertinent, let her go on, but jot down your questions on your notepad so you will remember to ask it later.

- If your narrator does stray into subjects that are not pertinent (the most common problems are to follow some family member's children or to get into a series of family medical problems), try to pull her back as quickly as possible. "Before we move on, I'd like to find out how the closing of the mine in 1935 affected your family's finances. Do you remember that?"

- It is often hard for a narrator to describe people. An easy way to begin is to ask her to describe the person's appearance. From there, the narrator is more likely to move into character description.

- Interviewing is one time when a negative approach is more effective than a positive one. Ask about the negative aspects of a situation. For example, in asking about a person, do not begin with a glowing description. "I know the mayor was a very generous and wise person. Did you find him so?" Few narrators will quarrel with a statement like that even though they may have found the mayor a disagreeable person. You will get a more lively answer if you start out in the negative. "Despite the mayor's reputation for good works, I hear he was a very difficult man for his immediate employees to get along with." If your narrator admired the mayor greatly, she will spring to his defense with an apt illustration of why your statement is wrong. If she did find him hard to get along with, your remark has given her a chance to illustrate some of the mayor's more unpleasant characteristics.

- Try to establish at every important point in the story where the narrator was or what her role was in this event, in order to indicate how much is eye-witness information and how much based on reports of others. "Where were you at the time of the mine disaster?" "Did you talk to any of the survivors later?" Work around these questions carefully, so that you will not appear to be doubting the accuracy of the narrator's account.

- Do not challenge accounts you think might be inaccurate. Instead, try to develop as much information as possible that can be used by later researchers in establishing what probably happened. Your narrator may be telling you quite accurately what she saw. As Walter Lord explained when describing his interviews with survivors of the Titanic, "Every lady I interviewed had left the sinking ship in the last lifeboat. As I later found out from studying the placement of the lifeboats, no group of lifeboats was in view of another and each lady probably was in the last lifeboat she could see leaving the ship."

- Tactfully point out to your narrator that there is a different account of what she is describing, if there is. Start out by saying, "I have heard ..." or "I have read ..." This is not to challenge her account, but rather an opportunity for her to bring up further evidence to refute the opposing view, or to explain how that view got established, or to temper what she has already said. If done skillfully, some of your best information can come from this juxtaposition of differing accounts.

- Try to avoid “off the record” information — the times when your narrator asks you to turn off the recorder while she tells you a good story. Ask her to let you record the whole things and promise that you will erase that portion if she asks you to after further consideration. You may have to erase it later, or she may not tell you the story at all, but once you allow "off the record" stories, she may continue with more and more, and you will end up with almost no recorded interview at all. "Off the record" information is only useful if you yourself are researching a subject and this is the only way you can get the information. It has no value if your purpose is to collect information for later use by other researchers.

- Don't switch the recorder off and on. It is much better to waste a little tape on irrelevant material than to call attention to the tape recorder by a constant on-off operation. For this reason, I do not recommend the stop-start switches available on some mikes. If your mike has such a switch, tape it to the "on" position — then forget it. Of course you can turn off the recorder if the telephone rings or if someone interrupts your session.

- Interviews usually work out better if there is no one present except the narrator and the interviewer. Sometimes two or more narrators can be successfully recorded, but usually each one of them would have been better alone.

- End the interview at a reasonable time. An hour and a half is probably the maximum. First, you must protect your narrator against fatigue; second, you will be tired even if she isn't. Some narrators tell you very frankly if they are tired, or their spouses will. Otherwise, you must plead fatigue, another appointment, or no more tape.

- Don't use the interview to show off your knowledge, vocabulary, charm, or other abilities. Good interviewers do not shine; only their interviews do.

These tips are from Willa Baum's Oral History for the Local Historical Society (1971).

Fellows/Interns

This section provides information about graduate and post-graduate opportunities with the Oral History Center. For information on internship and other opportunities for undergraduates, please visit the K-16 section of this website.

Oral History Graduate Fellowship

We sometimes offer a summer fellowship to a graduate student enrolled in the University of California system. This fellowship provides an opportunity to conduct a longform life history interview, which will be archived at The Bancroft Library. The fellow will be mentored by an experienced oral historian, see the interview through from conception to completion, and will present on their project at the Oral History Center’s annual Advanced Institute, which takes place in August. If a fellowship is available in a particular year, that will be noted here, along with application instructions.

Read reflections from the OHC’s 2019 graduate student fellow, Rudy Mondragón in “The Heart Beat of Our People:” My Experience With a World Champion. As an OHC graduate student fellow, Mondragón conducted a life oral history with professional boxer Kali “K.O. Mequinonoag” Reis. Mondragón went on to receive his doctorate from UCLA in Chicana/o and Central American Studies.

Internships

We do not have a formal internship program at this time. Please contact the director of the Oral History Center to inquire about other opportunities that might be available. (See the Overview page for contact information.)