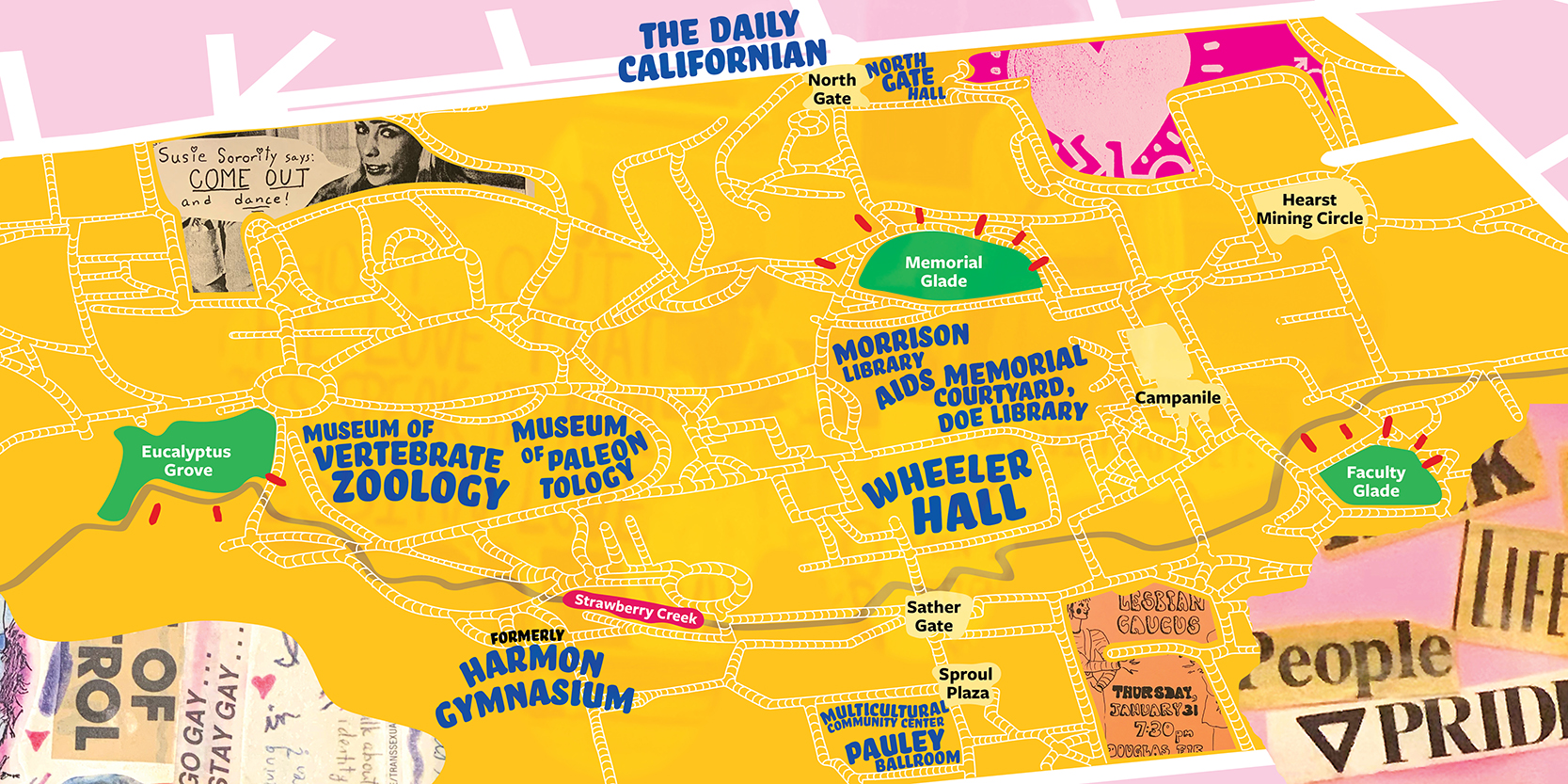

At UC Berkeley, queer history is all around us.

But if you’re casually strolling through the campus — and don’t know where to look — you might miss it.

We’ve mapped some of UC Berkeley’s LGBTQ+ landmarks, from historical hot spots to modern-day destinations. Visit the venue that hosted Cal’s first openly gay dance; learn the story behind two museums founded by a trailblazing benefactor (and prolific fossil hunter); and pay your respects in a tucked-away courtyard honoring those lost to the AIDS epidemic.

Alongside overviews, we’ve included resources from the UC Berkeley Library and beyond that illuminate the lore behind each location.

This list is by no means comprehensive. When possible, we chose locations whose stories are documented in the Library’s collections, but we looked to other resources to provide greater representation of identities across the LGBTQ+ community.

Explore the map and read on to learn more. You may never see the campus the same way again!

Editor’s note: This article includes references to sexual activity, and some of the featured resources contain mature themes and language.

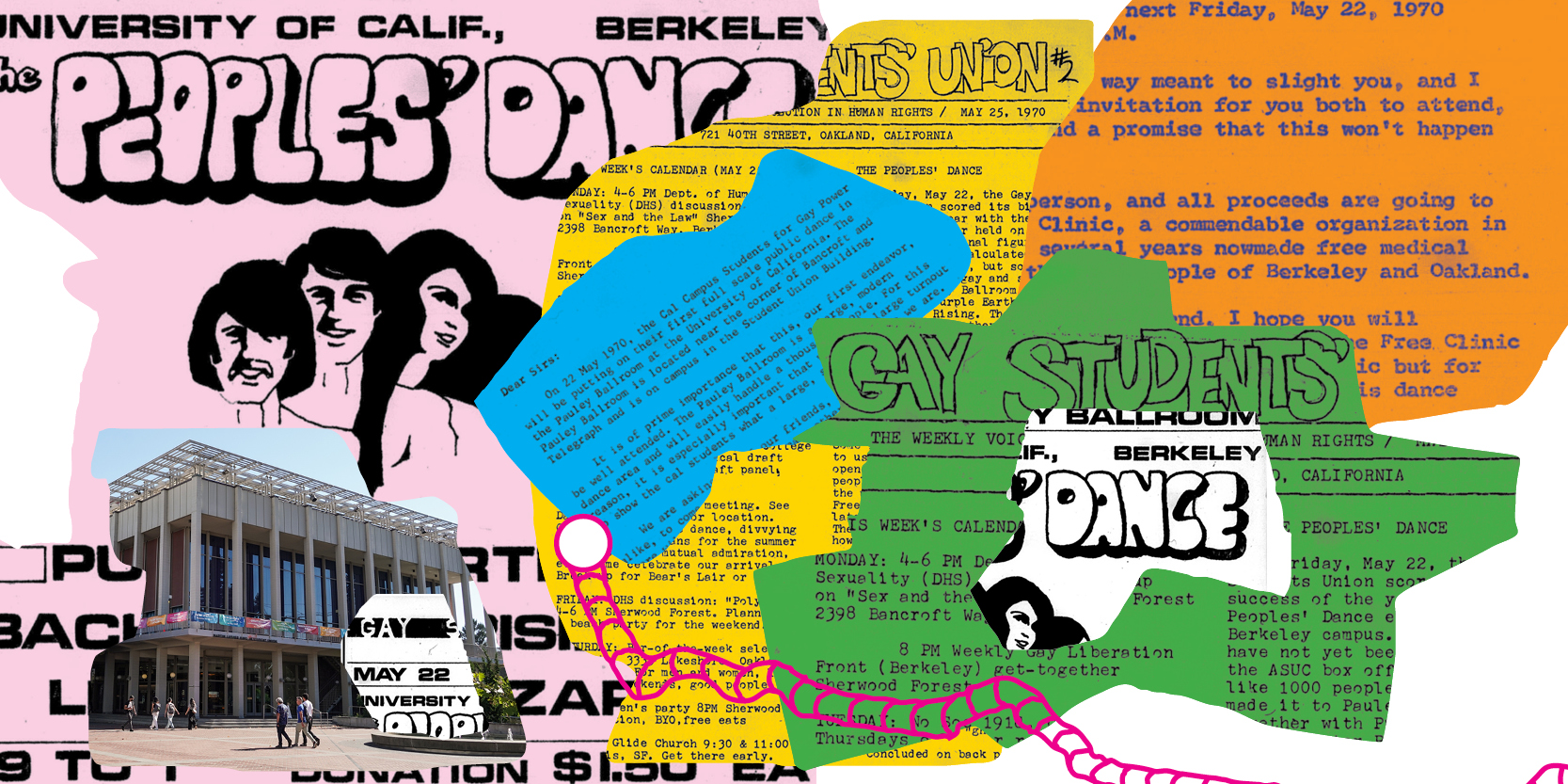

1. Pauley Ballroom

On May 22, 1970, Pauley Ballroom became the site of UC Berkeley’s first openly gay dance. The gathering lived up to its billing as the “Peoples’ Dance,” taking on a spirit of inclusiveness and acceptance. (The dress code? Anything from “dirty Levis to full suits or drag.”) According to The Daily Californian, Berkeley’s student newspaper, more than a thousand people — gay and otherwise — attended. But there was one notable absence. In the lead-up to the dance, thrown by the Gay Student Union, a KQED reporter asked Ronald Reagan about the gathering. “I haven’t been invited yet,” the governor quipped. In response, the group printed 100 invitation letters, to be circulated on Sproul Plaza for people to sign and send to the governor and first lady in Sacramento. In the end, the Reagans were no-shows.

Explore

- “Ronald Reagan,” Gay Bears: The Hidden History of the Berkeley Campus

- “Gaily, Gaily, But Guv Can’t Make It,” The Daily Californian, May 22, 1970

- “Gay Dance: Big Success,” The Daily Californian, May 25, 1970

- “Doe exhibit showcases Berkeley’s role in 1970s gay lesbian history,” Berkeleyan, Oct. 25, 2000

- Social protest collection, 1943-1982 (bulk 1960-1975)

Images in illustration: Social protest collection, 1943-1982 (bulk 1960-1975), BANC MSS 86/157 c, The Bancroft Library

2. Wheeler Hall

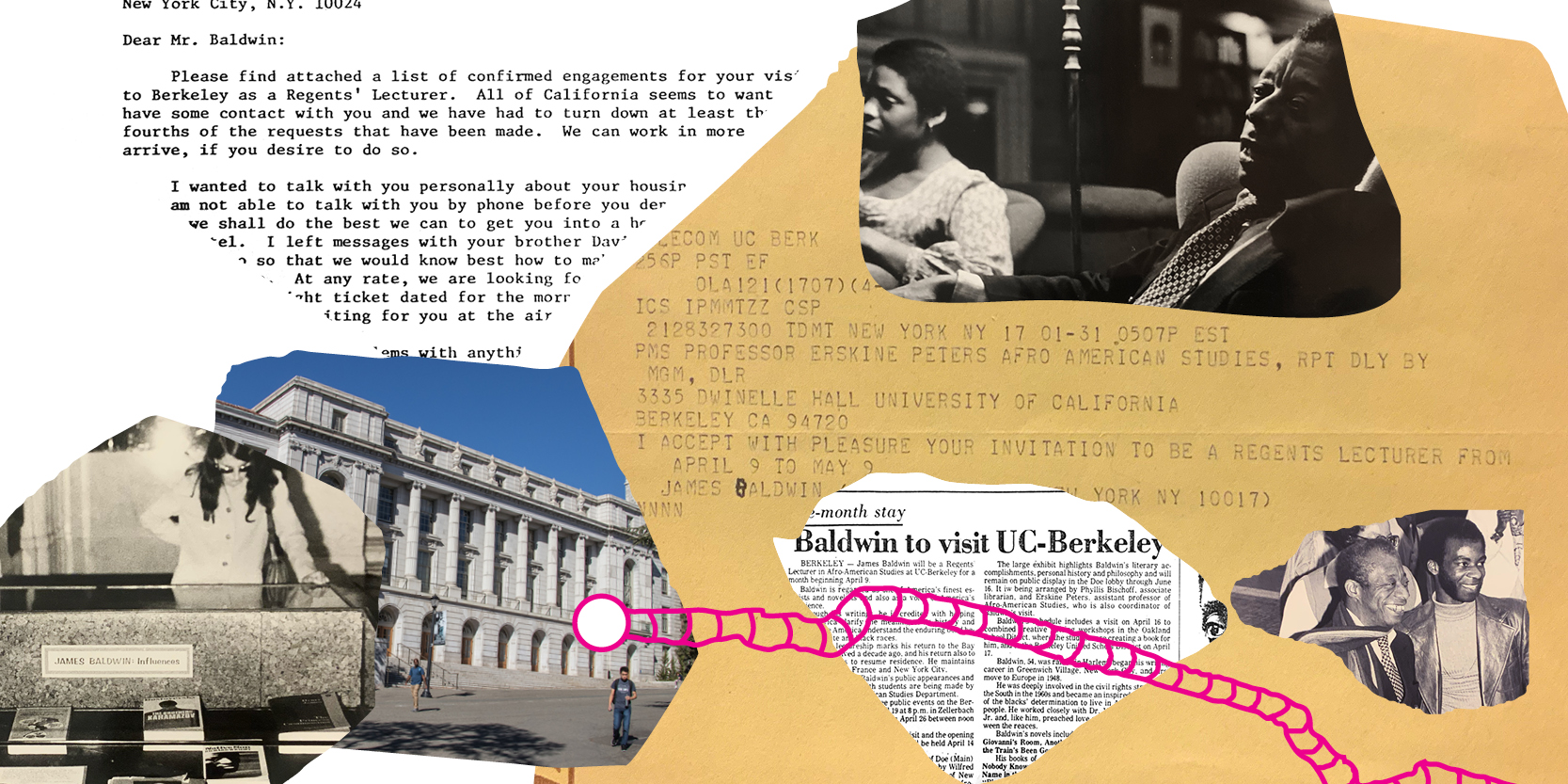

Designed by John Galen Howard, Wheeler Hall is a neoclassical gem. Over the years, Wheeler has hosted numerous events and luminaries befitting its grandeur. Civil rights activist and writer James Baldwin and French philosopher Michel Foucault, both LGBTQ+ icons, have filled Wheeler’s massive auditorium with their ideas, captivating audiences. (In honor of Baldwin’s 1979 visit, an exhibit in Doe Library paid tribute to his literary contributions.) In September of 2001, Wheeler was the site of a memorial service for Mark Bingham, an openly gay Cal alum and rugby player hailed as a hero for helping thwart the plans of the Sept. 11 hijackers aboard Flight 93, which ultimately crashed into a field in rural Pennsylvania. In 2002, mourners gathered in the auditorium to celebrate the life of June Jordan, a professor and poet whose work explores race and bisexuality.

Explore

- James Baldwin answers questions in Wheeler Hall, April 26, 1974

- James Baldwin speaks in Wheeler Hall, Jan. 15, 1979

- Correspondence and papers relating to the visit of James Baldwin

- Michel Foucault Audio Archive

- “Memorial Honors Professor’s Influence,” The Daily Californian, Sept. 16, 2002

Images in illustration: Correspondence and papers relating to the visit of James Baldwin to the University of California, Berkeley, CU-79, University Archives, The Bancroft Library; J. Pierre Carrillo/UC Berkeley Library

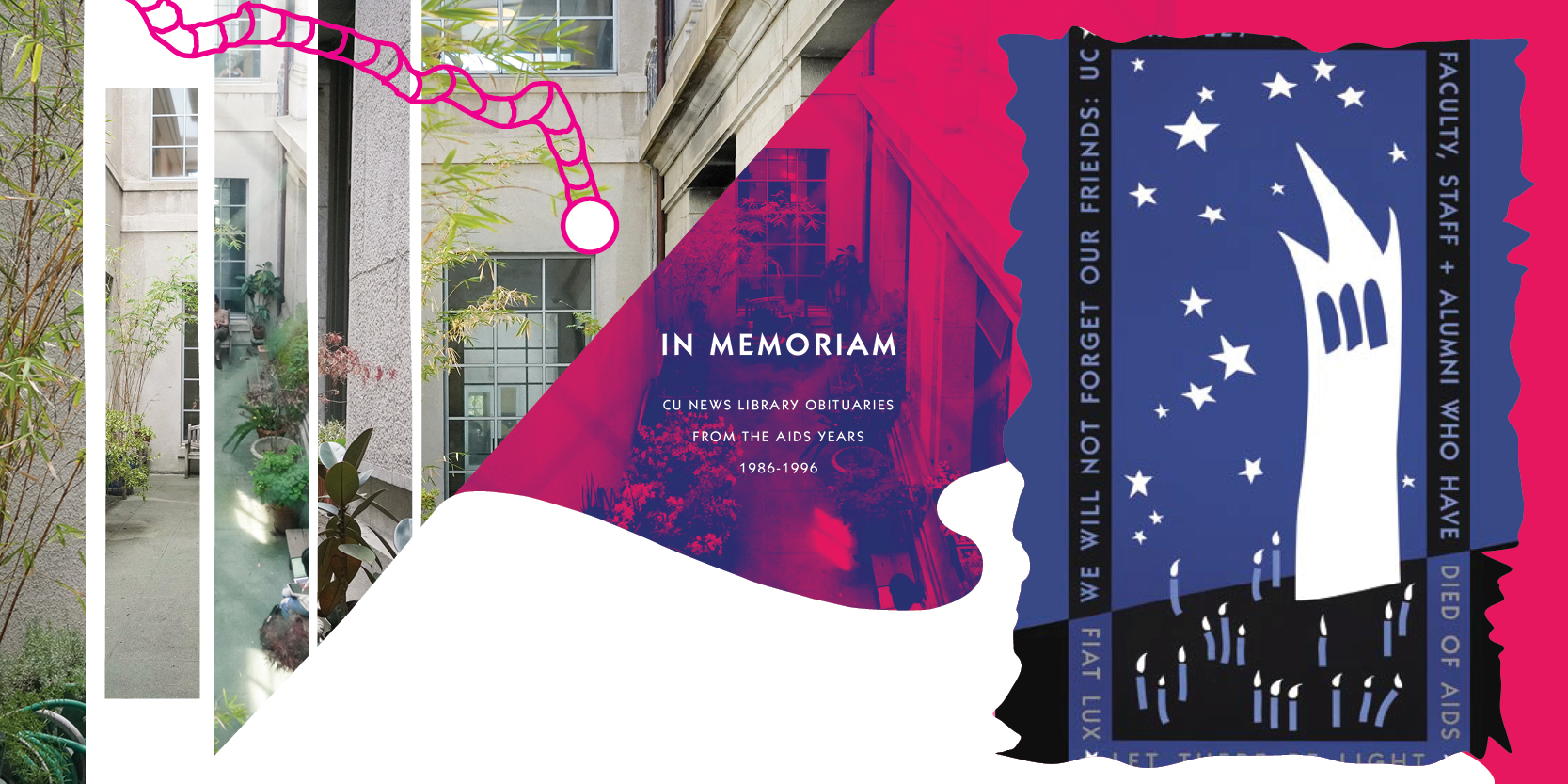

3. AIDS Memorial Courtyard, Doe Library

As the AIDS epidemic tore through the Bay Area in the waning decades of the 20th century, families, friends, lovers, and communities were quickly confronted with a new reality — symptoms and stigmas, hospital stays that were long then short, empty seats at dinner tables. A serene space, lined with wooden benches and plants, was built near Doe Library’s south entrance to honor members of the UC Berkeley community who died of the disease. In the span of 10 years, the Library lost nearly a dozen members of its staff to AIDS. A keepsake booklet published in 2009, held in the University Archives and available in digital form, serves as a tribute to the fallen members of the UC Berkeley Library family.

Explore

- In Memoriam: CU News Library Obituaries from the AIDS Years, 1986-1996

- “Inside information: 5 programs and places more people need to know at the UC Berkeley Library”

- Doe Library’s floor plan (AIDS Memorial Courtyard is on the first floor)

Images in illustration: In Memoriam: CU News Library Obituaries from the AIDS Years, 1986-1996. Minuteman Press, 2009.

4. Harmon Gymnasium

It started in a less-than-glorious location: the downstairs men’s bathroom at Harmon Gymnasium. By the late 1960s, the police had caught wind of the lavatory’s reputation as a destination for down-low dalliances. According to accounts in news reports, plainclothes police officers would “pretty themselves up,” linger in the lavatory, and coax men into engaging in lewd activity — before arresting them. Officers reportedly went as far as peering into holes and vents and under stalls for signs of impropriety. The number of arrests quickly climbed from one or two a month to quadruple that rate, according to the Berkeley Barb, the underground newspaper and voice of the counterculture. Students for Gay Power leapt into action, staging a protest in front of the gym, in an area now called Spieker Plaza. (The gym was reconstructed as Haas Pavilion, which opened in 1999.) The march, held in January of 1970, is believed to be the first Gay Liberation demonstration on the Berkeley campus. “(Students for Gay Power) want a society where Gays don’t have to cruise johns but can meet each other in open places just as straights can,” the Barb reported. “(But) the UC cops … are (expletive) things up almost liturally (sic).”

Explore

- “Gay Liberation Movement,” Gay Bears: The Hidden History of the Berkeley Campus

- “Students for Gay Power March on Harmon,” The Daily Californian, Jan. 23, 1970

- “Fan fires,” Berkeley Barb, Feb. 13, 1970, Page 5

- Here Are My People by David A. Reichard (access via Project MUSE with CalNet ID)

- Social protest collection, 1943-1982 (bulk 1960-1975)

Images in illustration: Social protest collection, 1943-1982 (bulk 1960-1975), BANC MSS 86/157 c, The Bancroft Library; UC Regents; The Daily Californian archives, The Bancroft Library; “Gay Liberation Movement,” Gay Bears: The Hidden History of the Berkeley Campus

5. The Daily Californian

Established in 1871, UC Berkeley’s student newspaper has a history that’s long, storied, and — yes — queer. In 1965, before the Gay Liberation Movement took wing, The Daily Californian published a landmark, and polarizing, series of articles chronicling homosexuality at UC Berkeley. The articles — penned by Feature Editor Konstantin Berlandt, who would go on to become the paper’s editor-in-chief — invited readers to peer into the subterranean lives of gay men, and included clear-eyed discussions about the closet, on-campus cruising, and the struggle for self-acceptance. A few years later, Berlandt succinctly set to words the yearning of a generation of fellow travelers, and too many that followed. “I’m not jealous of heterosexual love,” he wrote. “I’m jealous of heterosexual freedom.” Over the years, the Daily Cal has documented the pain, pride, and protests of the LGBTQ+ community, from early activism to first-person accounts of transgender students in the 21st century.

Explore

- “Daily Californian, 1965,” Gay Bears: The Hidden History of the Berkeley Campus

- “Minorities — ‘2700 Homosexuals at Cal,’” The Daily Californian, Nov. 29, 1965

- “UC Paper Names New Chief Editor,” San Francisco Examiner, June 1, 1968 (access via ProQuest with CalNet ID)

- “‘Gay Liberation’ Vows to Fight Oppression,” The Daily Californian, Oct. 20, 1969

- “Out Of The Closet,” The Daily Californian, Nov. 7, 1969

Images in illustration: The Daily Californian archives, The Bancroft Library

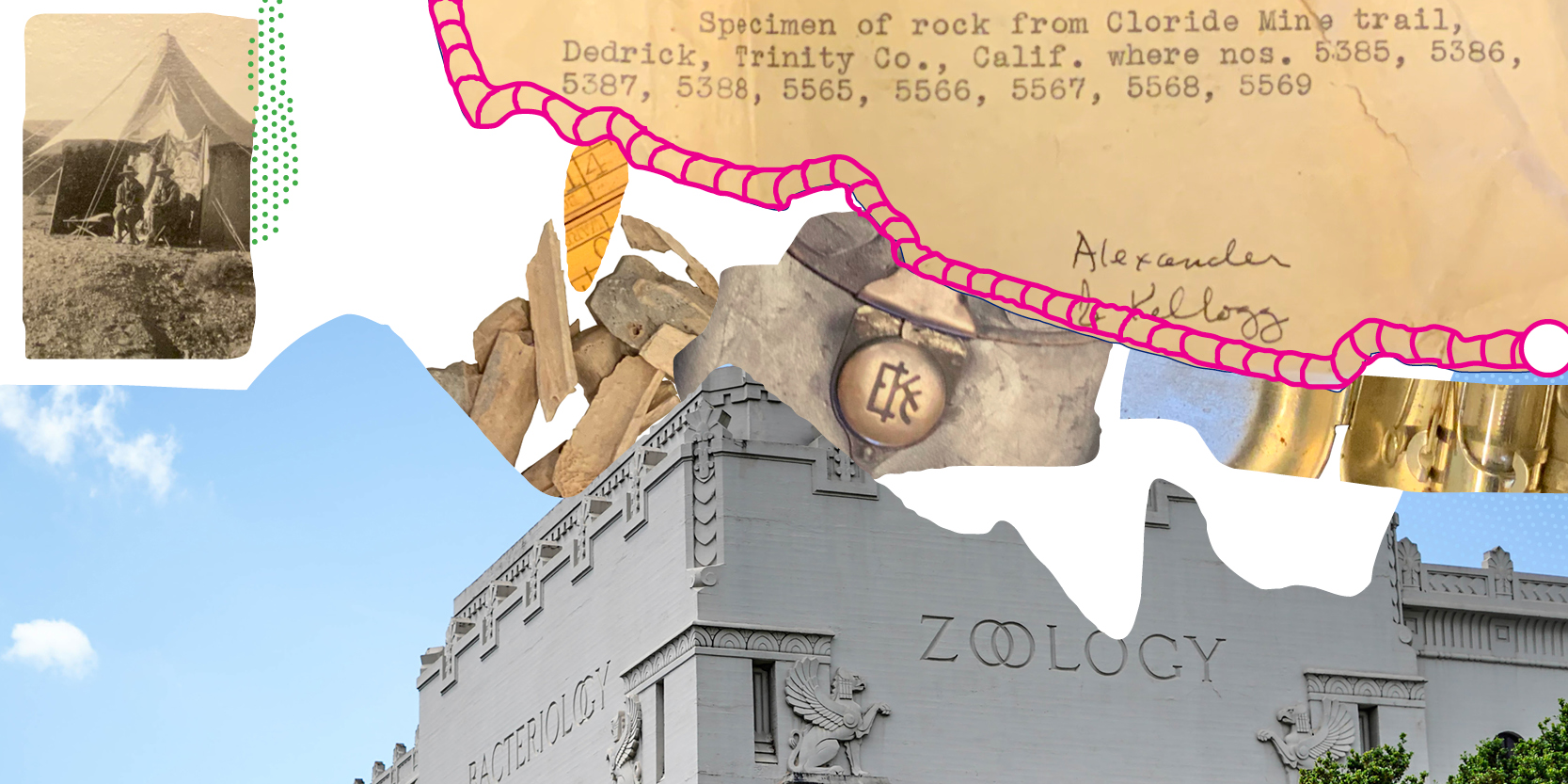

6 + 7. Museum of Vertebrate Zoology + Museum of Paleontology

Annie Montague Alexander’s taste for adventure started early. Born into a wealthy family in Honolulu, Alexander spent her younger years on the Hawaiian island of Maui, where she liked to hike and swim. Choosing excitement over practicality, she took particular pleasure in entering her bedroom by scaling up to the roof of the veranda and crawling into an open window instead of climbing the stairs. Her family relocated to Oakland in 1882. Ever inquisitive, Alexander attended lectures by John C. Merriam, assistant professor of paleontology at the University of California, fueling her interest in the field, and fanning the flames of her nascent wanderlust. Alexander was keen to pass along her passions: She largely founded and funded Berkeley’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology and Museum of Paleontology. (When Theodore Roosevelt, visiting campus as Charter Day speaker in 1911, was asked what he wanted to do for entertainment, he suggested visiting the zoology museum.) The sugar heiress was afforded freedoms uncommon to women of the time. She undertook many specimen-scouting sojourns, often with the companionship of Louise Kellogg, a University of California alum, with whom Alexander is believed to have had a close, even romantic, relationship. “(Alexander) was a lesbian,” a former employee at the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology stated in an oral history. “Her friend was Louise Kellogg and they did everything together to the end of their lives.” Today, both museums are living monuments to the power of curiosity, and to the life and contributions of Alexander, who was unfazed by new frontiers. The museums aren’t open to the general public, and their collections are used primarily for research purposes. Visitors to the Valley Life Sciences Building, however, can take in the museums’ public displays, including the towering Tyrannosaurus rex cast standing watch over the atrium.

Explore

- “Annie Alexander and Louise Kellogg,” Gay Bears: The Hidden History of the Berkeley Campus

- Annie Montague Alexander by Hilda W. Grinnell (access via HathiTrust)

- On Her Own Terms by Barbara R. Stein (access via Project MUSE with CalNet ID)

- Annie M. Alexander and Louise Kellogg object collection

Images in illustration: J. Pierre Carrillo/UC Berkeley Library; Annie M. Alexander and Louise Kellogg object collection, BANC PIC 2007.051--OBJ, The Bancroft Library; [Snapshot of Annie M. Alexander and Louise Kellogg camping at Last Chance Gulch, Kern County, Calif.], BANC PIC 2005.053--PIC, The Bancroft Library

8. Multicultural Community Center

Queer at Cal? You belong here. LGBTQ+ students can find support and kindred spirits through a range of organizations, including the Gender Equity Resource Center; the Queer Alliance and Resource Center; and the Multicultural Community Center. Support for transgender and nonbinary members of the Cal community includes a policy that ensures the accurate representation of someone’s lived name and gender; gender-affirming health care and transition support; safe and gender-inclusive housing; and gender-inclusive restrooms. The Transgender Student Wellness Initiative, a collaboration between the Gender Equity Resource Center and the Multicultural Community Center, is an effort by and for transgender and nonbinary students. The program cultivates leadership skills while serving the community through resources and activities, which have included communal meals, a workshop on self-compassion, and financial support for gender-affirming supplies.

Explore

- LGBTQ+ Resources (GenEq)

- “UHS offers gender-affirming treatment through SHIP, eTang portal,” The Daily Californian, June 27, 2024

- Transition Care Intake Form (for connecting students with transition care resources)

- Nonbinary @ Cal, UC Berkeley Life

Images in illustration: With permission from the Transgender Student Wellness Initiative

9. Morrison Library

Morrison Library, known as “the university’s living room,” is a world unto itself. Opened in 1928, Morrison is a walk-in time capsule within Doe Library where visitors can bliss out on music, art, books, and poetry. (Befitting its trip-in-time aesthetic, the library is a laptop-free zone.) LGBTQ+ luminaries from near and far — Ari Banias, Alex Dimitrov, Kay Gabriel, and others in recent years — have filled the space with their finely crafted poetry as part of the noontime Lunch Poems series. At a Lunch Poems event in early 2020, UC Berkeley Professor Emeritus Robert Hass, a former U.S. poet laureate and the founder of the series, read “Dancing,” powerfully invoking the 2016 shooting at a gay nightclub in Orlando, Florida, the deadliest mass shooting in U.S. history at the time.

Explore

- UC Berkeley Lunch Poems

- “‘From death to dreams’: Celebrated poet Robert Hass reads new collection for Lunch Poems series”

Images in illustration: UC Berkeley Events, YouTube

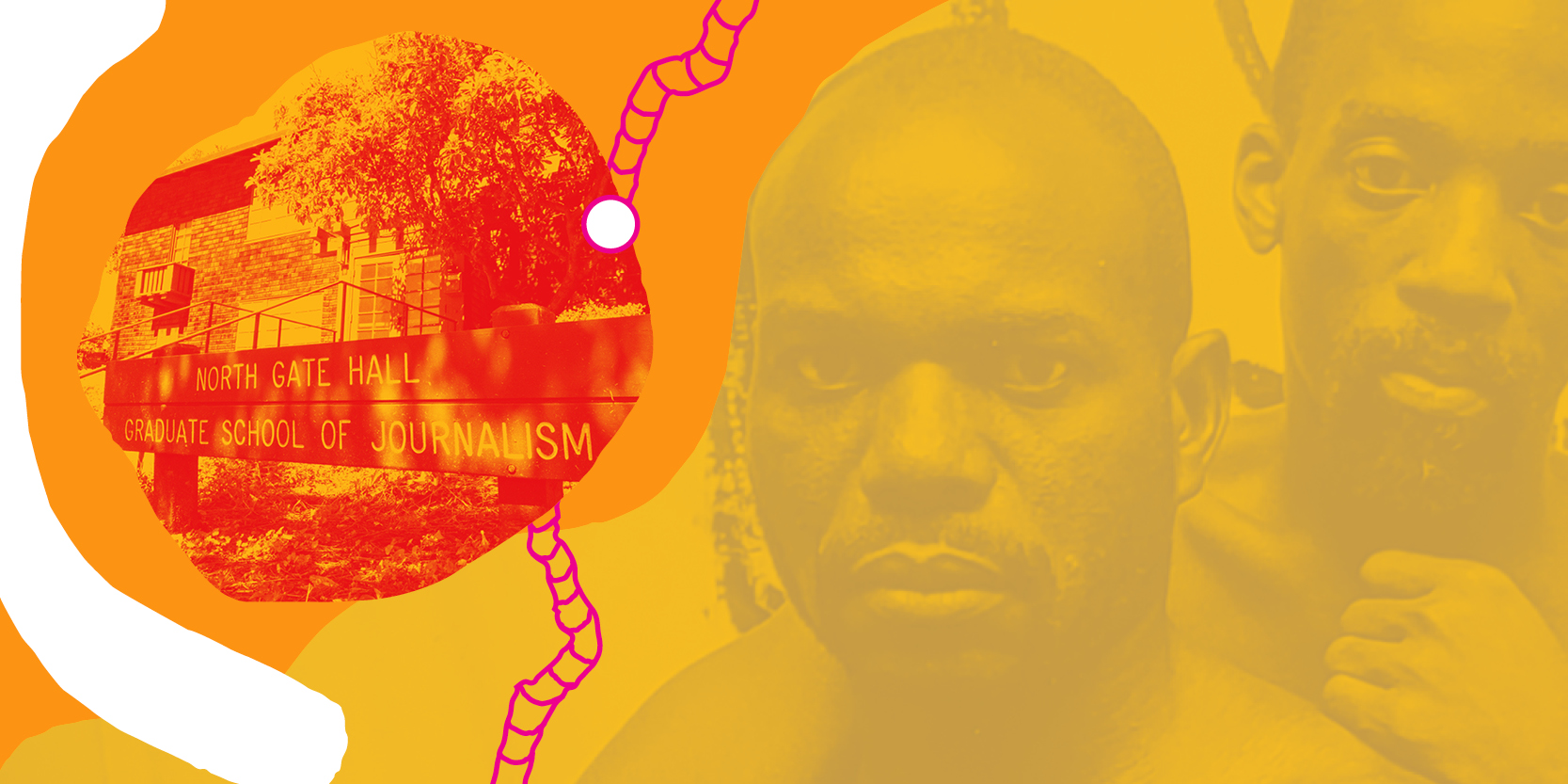

10. North Gate Hall

Marlon Riggs died not long after reaching his 37th birthday. But the accolades he earned, thoughts he provoked, and people he inspired would be enough to fill several lifetimes. Riggs studied American history at Harvard University, graduating magna cum laude in 1978. He went on to attend UC Berkeley’s Graduate School of Journalism, housed in North Gate Hall. Just six years after earning his master’s degree, he began teaching at his alma mater. Riggs earned tenure in 1992, and reportedly was one of the youngest tenured professors at UC Berkeley. Students loved Riggs, describing him as a mentor and “North Star” who encouraged them to make documentaries from the heart. As a filmmaker, Riggs broke new ground with virtually every project he undertook. By the end of his short career, he had earned an Emmy Award for Ethnic Notions, unpacking African American stereotypes from the antebellum period to the civil rights era; a Peabody Award for Color Adjustment, examining racism in the broadcast age; and the Berlin International Film Festival’s Teddy Award for best documentary for Tongues Untied, his experimental exploration of gay Black identities. As his health worsened, Riggs would deliver lectures to his students over speakerphone from his hospital bed. Upon Riggs’ passing in 1994 from complications of AIDS, the Graduate School of Journalism hosted a screening of Tongues Untied at North Gate Hall. Even as the end of his life — and a career of zooming in on society’s injustices — drew near, Riggs’ sense of fulfillment hadn’t dimmed. “I don’t feel like a minority,” he said. “I live a full and productive life. I give to people and they give back.”

Explore

- “Adjusting the image,” The Daily Californian, April 17, 1992

- “Filmmaker, Prof Dies of AIDS at 37,” The Daily Californian, April 8, 1994

- William Benemann collection of sexuality and gender miscellany, 1953-2011

Images in illustration: William Benemann collection of sexuality and gender miscellany, 1953-2011, BANC MSS 2012/101, The Bancroft Library; UC Berkeley