As people began to line up on the Berkeley sidewalk, you couldn’t help but think about the many Americans who had recently stood in line to make their voices heard in the presidential election.

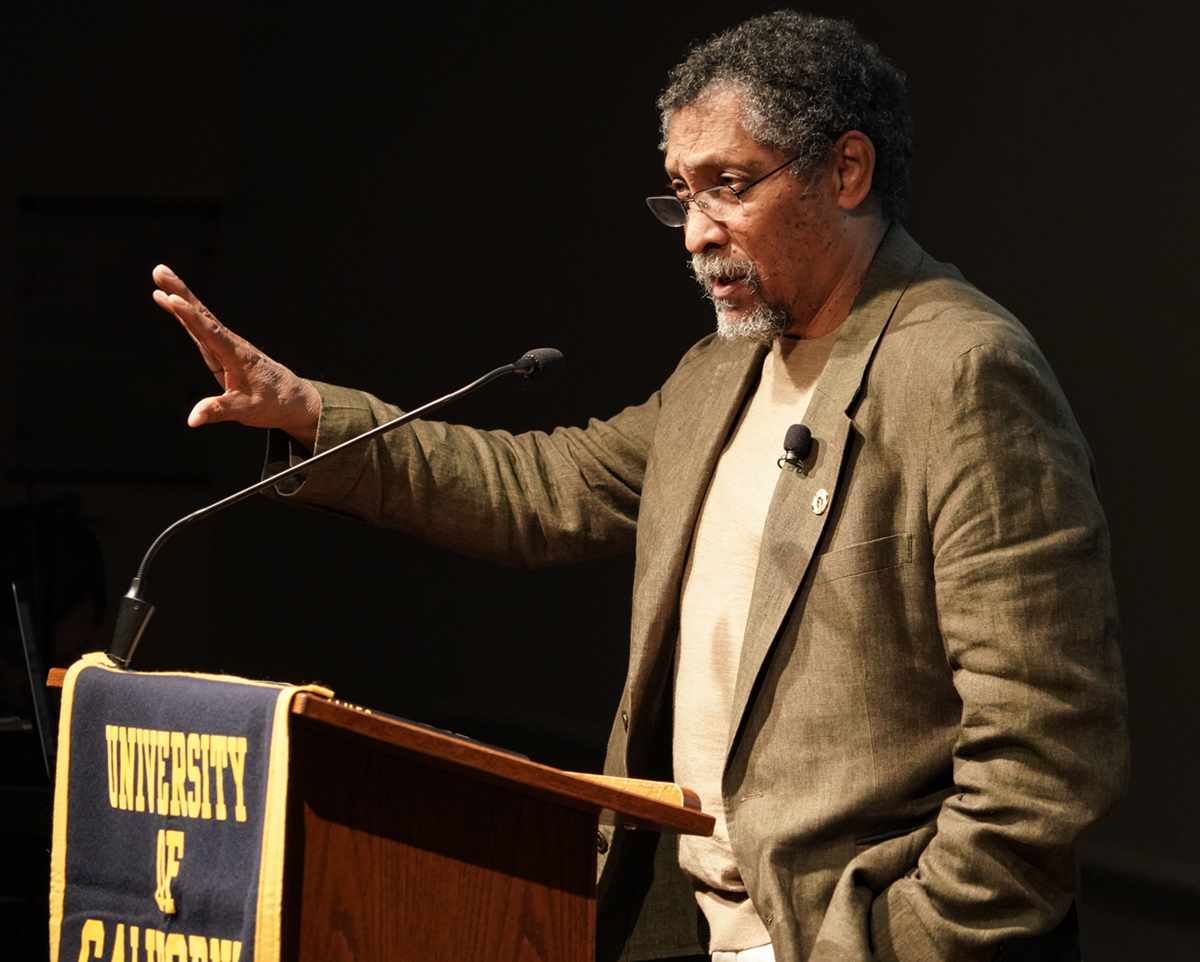

In a way, by showing up for a reading by esteemed author Percival Everett, mere hours after the election was decided, the gathered people were casting another vote — for the honest examination of American history and the importance of stories that offer a different perspective.

At the event, Everett read selections from his most recent novel, James, before taking questions from the engaged audience at the Magnes Collection of Jewish Art and Life. James is a radical reimagining of Mark Twain’s 1885 masterpiece, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, told from the point of view of Jim — or James, as readers learn he prefers — the enslaved man who joins Huck on a journey down the Mississippi River.

“To tell you the truth, I was really sick of books about slavery,” Everett said. “And so I tried to write a book that was not about slavery but about an enslaved person. And there’s a distinction there that I think is important. That was the power of the Adventures of Huck Finn in the first place, is that it’s the first time you have a character that represents an adolescent America, moving through a landscape, trying to deal with the experience that’s the most defining one of being American, which is race.

“So, I can say it now — especially because of the events in the last 24 hours (the presidential election) — that the more things change, the more they stay the same.”

Everett’s reading was sponsored by The Bancroft Library and its Mark Twain Papers & Project. Kate Donovan, director of the library, introduced Everett, calling him “one of the most prodigious and innovative writers of our time.” The author, who has penned more than 30 books, is also a distinguished professor of English at the University of Southern California.

James was recently awarded the prestigious Kirkus Prize for fiction. The New York Times bestseller has also been shortlisted for the National Book Award and the Booker Prize, the latest in a long list of accolades Everett has garnered over his career.

Donovan described James as “harrowing and sometimes humorous,” and said the retelling turns Twain’s classic of the American literary canon on its head.

“The novel gives expression to James’ voice, the depth and complexity of his world, and his humanity,” she said. “It is electrifying. I would argue it is a must-read of American literature. And I would not be surprised if it joins the canon also — and it should.”

Language as power

For a book that is likely to show up in the literary section of your local bookstore, James is filled with enough twists and turns for a thriller.

Among its many reveals — most of which won’t be shared here — is the way that enslaved people use language as both a means of expression and disguise. James and other enslaved characters speak in a heavy dialect (of the type you might recall from Huckleberry Finn) when talking to white people. But they speak without the dialect when conversing together, with James often narrating in a refined, intellectual voice.

“Safe movement through the world depended on mastery of language, fluency,” James says at one point in the novel, and several perilous moments in the plot hinge on which language he chooses to employ in a given context.

Everett was asked by one audience member whether that code-switching was based on historical fact, or simply an authorial choice.

“I don’t know what (the enslaved people) sounded like talking to each other,” he said. “But I do know that a very human thing is that enslaved, imprisoned, and oppressed people find ways to speak to each other that do not allow entry of their enemies. And that’s what that’s meant to represent.”

During another exchange, Everett spoke about language as a tool of power — what you choose to call a thing, how you direct attention to it, and how you choose to address it.

“I published a novel about lynching a couple of years ago called The Trees,” he said. “And I wrote it because we talk about lynching as if it’s a past practice in our culture. But the fact of the matter is, it’s a more practiced event than ever. We just have different names for it now. We call it police shootings or accidental shootings.”

Everett also cited the move by some states to reframe the way they teach in public schools about slavery. He said his “favorite” of the recommended terms to replace the word “slavery” — one that he was not sure had actually been adopted — was “involuntary relocation.” The phrase drew a gasp from the crowd.

Who gets to tell your story?

Reading James, on the other hand, you get the sense that nothing has been whitewashed. Even as a work of fiction, the book reads with the precision and clarity of authentic experience.

In Everett’s protagonist, you find a man who longs to tell his own story. At one point in the narrative, James is given a pencil, a gift that he later learns has come at a great cost. James clings to the nub as he navigates a series of escalating dangers. During a respite in his journey, he uses the pencil for the first time.

My name is James. I wish I could tell my story with a sense of history as much as industry. I was sold when I was born and then sold again. My mother’s mother was from someplace on the continent of Africa, I had been told or perhaps simply assumed. I cannot claim to any knowledge of that world or those people, whether my people were kings or beggars. I admire those who … can remember the clans of their ancestors and their names and the movements of their families through the wrinkles, trenches, and chasms of the slave trade. I can tell you that I am a man who is cognizant of his world, a man who has a family, who loves a family, who has been torn from his family. A man who can read and write, a man who will not let his story be self-related, but self-written.

With my pencil, I wrote myself into being.

For Donovan, letting people tell their own stories is essential to The Bancroft Library’s work. She emphasized the importance of people being able to see themselves and their communities in the collections at the library.

“Documenting and preserving and sharing these diverse stories, I think, is really critical for us to better understand and learn about the complexities of the past,” she said. “We need that knowledge, I believe, to tackle the challenges that we have today, and to look toward tomorrow so that we might shape a better and more just future for ourselves and our communities.”

Given that mission, Donovan said it’s not surprising that the library holds the papers of many writers — from Maxine Hong Kingston to Lawrence Ferlinghetti to Joan Didion, and, of course, Mark Twain.

Bancroft’s Mark Twain Papers & Project traces its origins to 1949, when the University of California received a voluminous archive of the private papers of Samuel Clemens. (Mark Twain is the writer’s pen name.) That collection has grown to include hundreds of original documents, thousands of letters, and copies of everything else Twain is known to have written, according to Donovan. The project even has what is believed to be a lock of the author’s hair.

“These extraordinary collections make the Mark Twain Papers & Project the center for the world’s study of Mark Twain’s writing and legacy,” Donovan added.

When Spielberg comes knocking

Everett’s book — perhaps his most popular to date — continues to shine light on Twain’s legacy as well. And both authors are about to get an even bigger boost, with the recent announcement that Steven Spielberg’s Amblin Entertainment is slated to produce an adaptation of James for Universal Pictures. Taika Waititi is in talks to direct the film, according to multiple sources.

It’s not the first adaptation of Everett’s work for the silver screen.

His 2001 novel, Erasure, was the basis for the 2023 film American Fiction, which was awarded the Oscar for best adapted screenplay. The satirical story is about the exploitation of Black artists by the entertainment industry. Cord Jefferson directs the movie, and Jeffrey Wright stars in it.

When asked how he feels about having his books adapted, Everett drew a clear line between the two works of art.

“A film is not my book,” he said. “I have written my book. It’s exciting to me that someone has found something that I have made and used it as a source to make another work of art. I happen to like Cord Jefferson’s American Fiction. And I say ‘Cord Jefferson’ there because it’s his film.”

That separation may be made easier by the fact that Everett claims to have a kind of amnesia when it comes to his own work, which he confesses may be a defense mechanism.

“I don’t remember books after I finish them,” he said. “I have what I call the mama bear school of art. That is, when I’m done with a book, I push it away. If it can … survive, that’s great. But it cannot come back to the den.”

While Everett may not remember what he writes, his loyal readers are rewarded again and again by work that is as trenchant as it is unforgettable.