Spilling across the diary’s pages are the thoughts and dreams of a teenage boy.

Reflections on daily activities and adolescent milestones — pingpong and basketball, dancing at a party for the first time and the perpetual quest for good grades — are interspersed with neatly shaded drawings, and hopes of one day becoming an artist.

Reality creeps in, tearing through the casual tone and immaculate handwriting.

“I shall remember that day that I was evacuated for the rest of my life,” Stanley Hayami, 17 years old at the time, writes on May 14, 1943, at the Heart Mountain concentration camp in Wyoming, reflecting on his first year of incarceration. “I shall remember the barbed wire, the armed guards, the towers, the dust, the visitors, the food, the long lines, the typhoid shots.”

But one passage in particular, written in stark all-cap block letters, caught the eye of Ryan Gottschalk ’25, who studies history at UC Berkeley.

“I don’t tell this to anyone because they’ll figure that I’m a queer (maybe I am),” Hayami writes in an entry dated June 27, 1943, threading together feelings of alienation and an aching desire for solitude.

“It took me right back to my own years of teenage angst, thinking about coming out and struggling with my sexuality,” Gottschalk says. “It’s really amazing that, you know, somebody existing in the 1940s, who in many ways is so separated from us today, had such similar feelings.”

In his Library Prize-winning project, “Erased: An Exploration of Queer Japanese Americans’ Experience During the Internment Period,” Gottschalk provides a sensitive, nuanced reading of firsthand accounts, revealing clues into the presence of LGBTQ+ prisoners in the concentration camps. Through that work, along with the close examination of other sources, including records held by The Bancroft Library, Gottschalk adds brushstrokes to the harrowing portrait of Japanese American life during World War II, raising visibility, challenging assumptions, and pulling to the surface themes from the past that linger today.

Out of the shadows

With a decree in hand — Executive Order 9066, signed Feb. 19, 1942, by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt — the United States government rounded up more than 120,000 Japanese Americans, pushing them out of their homes and into concentration camps, euphemistically dubbed “relocation centers.” Scattered across the desolate, rugged landscapes of the country’s interior, the new arrivals were choked off from any semblance of normal life.

This large-scale displacement disrupted the family structure, a theme Gottschalk and his classmates explored in “Images of History,” a College Writing course that examines the incarceration of Japanese Americans and culminates in a research project. Because activities were often communal and organized by age group, young incarcerees often found themselves with more independence, out of the watchful eye of their elders.

“Hearing that made me reflect on my own experience growing up gay,” Gottschalk says. “Being able to separate yourself from your parents allows you to have a lot more space in exploring your own identity.”

Curiosity piqued, Gottschalk decided to explore queerness in Japanese American concentration camps for his class project.

His research journey began the way most digital age deep dives do: on Google. Upon searching, he quickly learned that existing literature on the topic was scarce, with some notable exceptions, including the work of scholar, artist, and writer Tina Takemoto.

Through Takemoto’s research, Gottschalk learned of Jiro Onuma, who emigrated from Japan to San Francisco in 1923, at age 19. During World War II, Onuma was imprisoned at the Topaz concentration camp, in a windswept desert in Utah. A modest collection of Onuma’s papers are held at the GLBT Historical Society in San Francisco. Among the personal effects are images, made both during and before the incarceration, of Onuma and a man named Ronald, who is believed to have been Onuma’s partner. In a double portrait of the two, likely made at a photo studio at Topaz, Onuma and Ronald are pictured alongside each other, Onuma with a gentle smile, and Ronald sporting a playful smirk.

The two men were separated when Ronald was sent to Tule Lake, a concentration camp in the far-northern climes of California designated for “disloyal” prisoners. Onuma received a photo of Ronald at the camp, pictured with two other men. If Onuma and Ronald were indeed lovers, the photographs in Onuma’s collection would be the only known images of gay Japanese American men, and of a same-sex Japanese American couple, incarcerated during World War II. Aside from the photographs, Onuma kept a collection of bodybuilding magazines, “despite not being much of a bodybuilder himself,” Gottschalk says, as well as thinly veiled gay erotica.

Evidence of queerness in institutional records was scant but revealing. Gottschalk searched The Bancroft Library’s Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Records — a massive collection of documents, diaries, letters, and reports — only to find 14 instances of the word “homosexual.” Of those mentions, a single one was in a document from camp administration. The document, a report from a 1943 meeting of the social welfare office at the Poston concentration camp, in Arizona, recounts the story of a 14-year-old girl who had “turned to homosexual practices,” reportedly after being spurned by boys. “She is interested in all the little girls on the block and has given them sex information and has taught them masturbation,” the report states. “The problem is so acute that about 25 are involved.” A discussion ensues, with “lack of playground equipment” proffered as a possible explanation for the behavior.

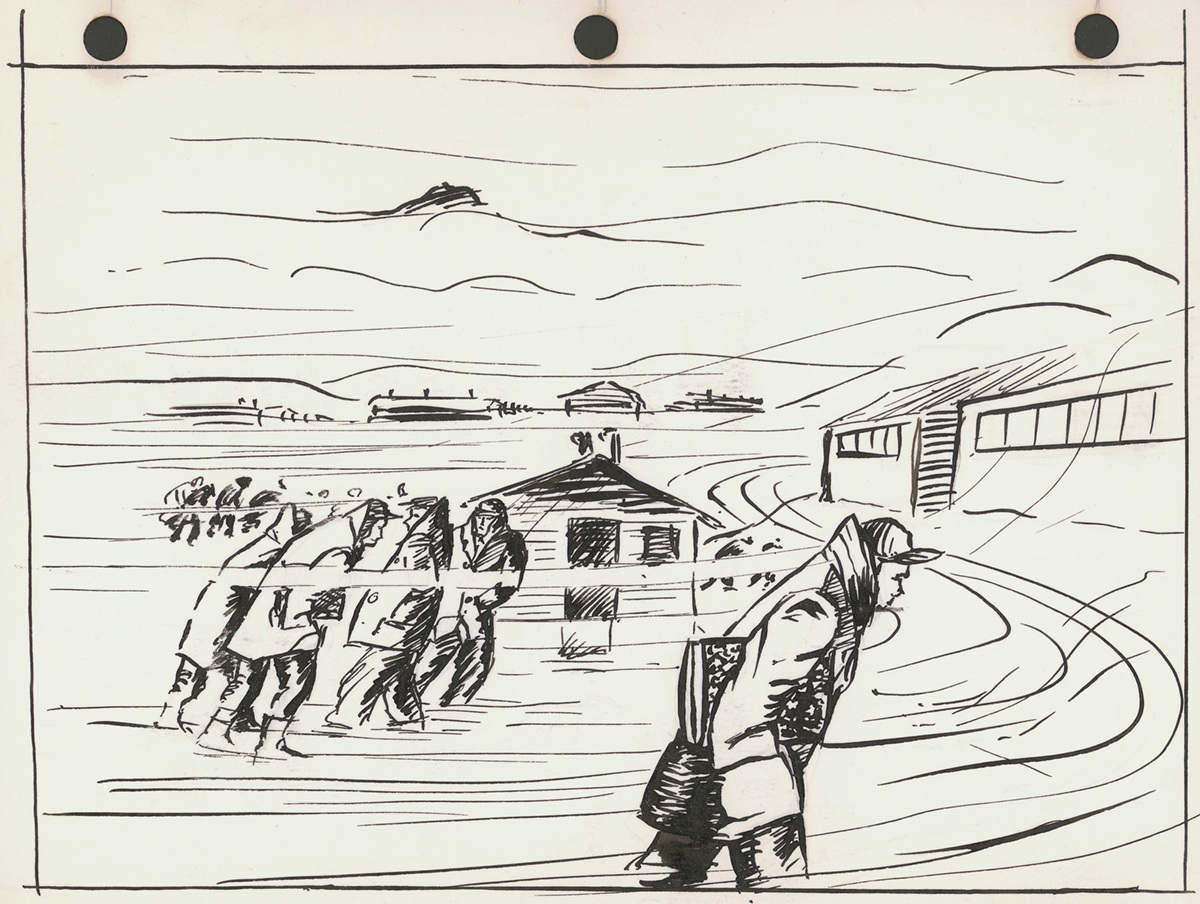

And then there are the written accounts by incarcerees themselves. Through the UC Berkeley Library, Gottschalk found a strategy outlined by scholar Hanna Kubowitz for parsing coded queer themes in literature. He used it to identify possible queer themes in the diary of Stanley Hayami, the 17-year-old in Wyoming who made what could be interpreted as a startling-for-the-time confession in the pages of his diary. But it wasn’t just the words that Gottschalk found intriguing: Sandwiched between Hayami’s earnest written entries are many drawings, from cartoonish figures to a moody scene of the concentration camp at night. In all of the aspiring artist’s sketches, the likeness of a woman appears only once: Everyone else portrayed by Hayami is a man, including a strikingly detailed squiggle-shaded muscle-bound nude.

Hayami wouldn’t live long enough to realize his artistic ambitions. He went on to join the Army, showing loyalty to a country that denied the same to him. He left Heart Mountain in June 1944, and was killed in northern Italy in April of 1945, while trying to help a comrade. During his research, Gottschalk found inspiration and kinship in the pages of Hayami’s diary, which he read twice in its entirety.

“Even if he wasn’t queer, he clearly struggled with his own identity and with relating to other people,” Gottschalk says. “And as a gay man, that was very, very relatable to me. And I just thought it was so human, that it really made me want to expose these stories and this part of history that had been totally ignored.”

Gottschalk also applied Kubowitz’s framework to the 1946 book City in the Sun, a fictionalized account by Karon Kehoe, a white woman who had taken the last name of her same-sex lover, Monika Kehoe. Because of their shared surname, Karon was able to pass herself off as Monika’s half-sister, so they could live together in Arizona’s Gila River concentration camp. Karon and Monica Kehoe’s relationship itself supports the existence of queerness in Japanese American concentration camps, and the book provides further clues through its not-so-subtle homoeroticism, as Gottschalk points out. One particular passage, depicting an initiation ritual among boys in a shower room, uses ambiguous language, but “it’s pretty clear that this is some sort of sexual liaison,” Gottschalk says.

“Coke (the adolescent protagonist) talks about the shame and excitement that he feels in seeing this experience,” Gottschalk says. “This, to me, read as a subtextual but pretty obvious example of queerness.”

The inclusion of homoerotic themes in a book that was released shortly after the author’s own incarceration experience, and that was praised for its accuracy by Japanese American readers, may be an indication that scenes like the ones depicted by Kehoe actually happened in the concentration camps, “at least to some extent,” Gottschalk says.

‘A gap in the record’

It’s not fair, nor particularly historically accurate, to default to heterosexuality when thinking about the people who came before us, Gottshchalk says.

“From the dawn of human history, queerness has been an innate part of human existence,” he says. “When you realize that, … I think it helps you get away from this presumption that ‘normal’ people throughout history are heterosexual, and thus homosexuality, transness, bisexuality, queerness — all of this — is somehow something that’s new and deviant and moving away from tradition, whatever that means.”

The incarceration of Japanese Americans is extraordinarily well documented, which makes the scarcity of evidence of queerness in the concentration camps all the more glaring. And, yes, some of the pieces of evidence of LGBTQ+ behavior or identity are less than overt, but that doesn’t mean they should be cast aside, Gottschalk says.

“Our modern conception of sexuality is that it’s something that you’re born with, and that is this integral part of your identity,” he says. “They’re all relatively new concepts that would have been foreign to queer people of this time.”

Repression could be a major reason LGBTQ+ incarcerees are all but invisible in the historical record, Gottschalk contends. Japanese Americans, already treated as disloyal outsiders by the government, may have felt extra pressure to blend in to the mainstream culture, which meant hewing to heterosexuality, at least outwardly.

And camp administration may have contributed to the erasure, too. In a telling exchange, which Gottschalk discovered in Bancroft’s records, a camp administrator pushes back against a visiting doctor’s suggestion that the number of homosexuals in a particular camp is on par with the proportion that you’d see anywhere. In downplaying the presence of “practising” homosexuals, the administrator cites the lack of “violent sex crimes such as rapes,” invoking a homophobic stereotype. (Notably, the concentration camp at the heart of the exchange is the same one in Arizona where queer behavior had already been observed and recorded.)

For his work, Gottschalk won the Charlene Conrad Liebau Library Prize for Undergraduate Research. Since 2003, the prize has celebrated excellence in Library research. It is made possible by an endowment from Charlene Conrad Liebau ’60, a Rosston Society member of the Library Board.

“While the Library Prize serves to recognize the work of students, I hope it also serves to encourage students to pursue an interest — to research in depth and to learn, as Ryan Gottschalk demonstrates,” Liebau says. “And perhaps, along the way, make a discovery and thus add to our body of knowledge.”

Gottschalk’s research is not only a powerful contribution that provides a fuller understanding of Japanese American incarceration — it’s also moving and inspiring, says Pat Steenland, who taught the College Writing course that set in motion the project that earned Gottschalk the Library Prize.

“This is the kind of research that really makes a difference, when somebody identifies a gap in the record,” she says. “I think that’s really an incredible thing to have done.”

Looking back, Gottschalk remembers a time when he scrapped his topic altogether, discouraged by the dearth of information. He shifted his focus to the long-term economic effects of incarceration on Japanese Americans, and gathered an impressive set of primary sources documenting financial losses. But a conversation with Steenland inspired him to stick to his original project.

“She was like, ‘Ryan, I know the topic that you’re actually very passionate about,’” he recalls his instructor saying.

Everyone has their own interests, and Steenland encourages her students to follow the research path that calls to them. As part of her class, she connects students with a trove of primary sources, including materials from the Library, in partnership with librarian Corliss Lee, who helped design a research guide for the course, and Theresa Salazar, Bancroft’s curator for Western Americana. When students are confronted with these artifacts from history, Steenland says, they often find something — a photograph, an advertisement in a newspaper, or, in Gottschalk’s case, a yawning void in the historical record — that captures their imagination, and gets the gears turning.

“You can’t make yourself be curious about something that you’re not curious about,” she notes. “But when you see the curiosity, especially in that moment, that’s when the spark happens.”