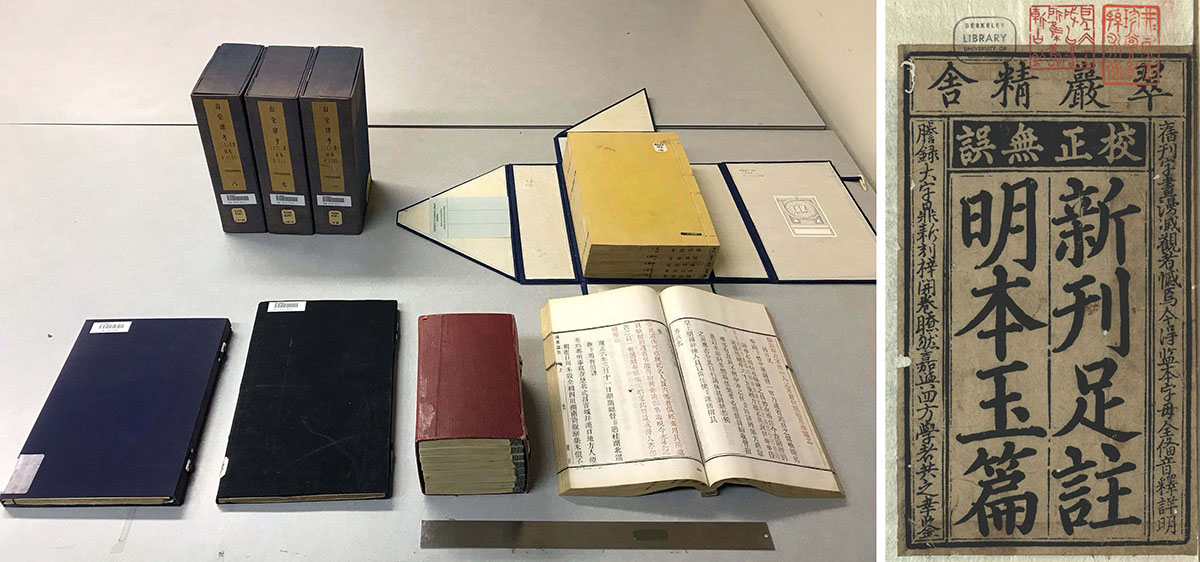

The books, printed centuries before Gutenberg mania swept through Europe, are some of the oldest in UC Berkeley’s collections.

In fact, some are among the oldest books, period.

“These are priceless materials,” said Peter Zhou, director of Berkeley’s C. V. Starr East Asian Library, or EAL. “Some of them are the only pieces of that publication in the world — the world has only one copy.”

And soon, these treasures, and more, will be free for anyone in the world to see.

Today, the UC Berkeley Library announces a monumental collaboration with Sichuan University, with funding from the Alibaba Foundation. The project aims to digitize most of the pre-1912 Chinese language materials from EAL’s collections, bringing them to life in vivid detail for researchers today and for generations to come.

While chunks of EAL’s collections have been digitized and made available online over the years, the project with Sichuan University is the first of its kind because of its grand scope. Berkeley’s collection of Chinese volumes is one of the largest among research libraries in North America. Nearly 10,000 titles are from before 1912, and are in line to be digitized.

Under the agreement, Berkeley will digitize half a million pages per year for three years, with the possibility of the project continuing for another three years after that. The digitization work, to be done in-house at Berkeley, will capture images in high resolution, meeting or exceeding current standards for digital scholarship collections and long-term digital preservation. Each digitized treasure will be painstakingly enriched with information, or metadata — for example, when the item originated or other notes that illuminate its history.

The images will be converted to text through a process called optical character recognition, or OCR. OCR opens the door to needle-in-a-haystack keyword searches within an item, and lowers the barrier of access for people with print disabilities. Sichuan University and DAMO Academy, Alibaba’s research institute, have developed a cutting-edge system that harnesses machine learning to convert ancient Chinese characters into machine-readable text. The system is quick and efficient, recognizing characters 30 times as fast as a human can read, with 97.5 percent accuracy.

At Berkeley, the materials will then make their way to the Library’s Digital Collections portal, where they can be examined 24/7, by anyone, from anywhere.

Among the treasures — which include old and rare woodblock editions and manuscripts — are volumes printed from blocks engraved in the Song and Yuan dynasties. According to Zhou, North American libraries hold around 120 titles tracing back to these periods, which saw the birth of large-scale printing over a thousand years ago. Of those titles, Berkeley holds 44, or roughly a third.

For many of the materials, this new digital life marks the next phase in a great journey through time and space. Some of the volumes have lived through periods of political upheaval and disaster, such as bombings in World War II, before making their way to EAL’s collections.

“These things have survived centuries,” said Deborah Rudolph, EAL’s curator of rare books and special collections. “They have gone from one collector’s collection to another. Sometimes those collectors have left materials behind because they’re fleeing civil war, sometimes they had reversals of fortune, so they had to sell the stuff. …

“It’s just incredible what some of this material has gone through.”

Beyond bringing a trove of easily searchable treasures to scholars, enthusiasts, and amateurs alike, enabling endless deep dives, the project is also notable for uniting institutions that are half a world apart for a common cause.

“This is a great step forward,” said Salwa Ismail, who, as associate university librarian for digital initiatives and information technology, oversees the Library’s Digital Lifecycle Program, which aims to broaden scholars’ access to Library materials online. “It’s an exciting partnership between two libraries in two different countries that allows for an open exchange of information, and an open exchange of rare materials, in a language that is so richly represented in our collections.”

While the push for open access has reached many corners of the globe, it hasn’t fully taken root in China yet. But one project at a time, the Library is taking the lead, planting seeds for a world where open access is the norm and, in the process, setting an example for others.

“Everybody understands that this is not an overnight project,” Zhou said. “But a long journey starts with the first step. …

“And now, we’re starting this long journey.”